Yet Another Archetypal ECS Rust Implementation

Intro

One of the first problems I encountered when making my game engine was how to handle game logic. I was already familiar with Unity’s GameObject and Component system, where your game world would contain multiple “GameObjects” that each have their own “Components” that would apply specific game logic to their owning objects (or others in the world).

%%{ init: { 'flowchart': { 'curve': 'stepBefore' } } }%%

flowchart LR

A[Game World]

A --> GM1[Game Object 1]

A --> GM2[Game Object 1]

A --> GM3[Game Object 1]

GM1 --> C1[Component 1]

GM1 --> C2[Component 2]

GM2 --> C3[Component 1]

GM3 --> C4[Component 2]

This method works fine for the most part, but scales terribly when you have thousands of components that have computationally expensive logic. This also makes parallelism and multithreading a bit more complicated since you can’t easily parallelize a lot of cheap operations.

Note

Unity DOTS and Unity ECS fix this completely since they use both multithreading and SIMD, but using their Job System.

So, for my game engine, I decided to implement a common (if not over-used) technique to alleviate these kind of problems: ECS ECS stands for Entity Component System, and it is an architectural pattern in use by game engines for handling a lot of game objects using multithreading safe methods. I am pretty sure that there are a multitude of articles and resources that explain how and why it is better for performance in general, but here’s my shot at explaining it. ECS is usually split into three parts: Entities, Components, and Systems.

Entities

Entities are simply just handles, like pointers, that point to something stored internally within the core of the engine. You can think of them as simple u64 integers or even a hexadecimal value (0x32).

Example

For example, any of these following values could be considered an entity

| 0x01 | 2 | 'E' | 0b0001 | 4294967295 |

|---|

As long as the values are unique and represent an integer at the end, these could all be used as Entity IDs (albeit it would be cursed to have a char be an entity ID lol)

Components

Components contain the data that is pointed to by each entity. Multiple components can be applied to entities, but there can only be one component “type” that can be applied to a single entity.

To be able to use our components internally, we must "indentify" each component from every other component. The simplest way to do this is to have a unique number (or unique value really) that is applied to each component type. How I handled this in my system is by So basically, we just have to think of our components as if they were an offset (left shift) of a singular bit inside a u64, which would differentiate them from every other component. Something like this basically:

| Component | ID Bitmask |

|---|---|

| Transform | 0b001 |

| Health | 0b010 |

| Player | 0b100 |

These values could be calculated with the following function (as long as you know the column index of each component)

Example

For example, I have this table over here that depicts my entities and components in my scene. I can apply a “Transform” component onto entity 01, and the “Health” and “Player” components onto entity 02, however, I cannot apply the “Player” component again into entity 02, since it was already applied. (using this table to represent our data makes understanding archetypes a lot easier later on)

| Entities | Transform | Health | Player |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entity 01 | X | ||

| Entity 02 | X | X |

These following structs could be a reasonable representation of the components above

// Position, rotation, and scale; all composited into one component

// Entity health component

;

// Components don't *need* to store data. They could be used for flagging entities for example

;

Systems

Systems handle logic. They iterate over entities or components and view them (read) or mutate (write) them using custom user implemented logic. This is what makes ECS easily multithreadable, since you would only need to turn this “Iteration” parallel (in Rust this is easily doable using the Rayon crate and the par_iter() or par_bridge() methods, which I will talk about a bit later on). Within my system I implement these as “queries'' that return an Iterator<T> over the components I wish to view or mutate.

Initial Naive Implementation

My initial implementation of ECS was quite scruffy however; it was solely single threaded, and was very naive. All I did was store a hashmap of unique u64s, which are my entities, and store a Vec<Box<dyn Component>> where Component is a trait implemented for each struct that I want to treat as a component. This worked fine at first but it scaled horribly. First of all it didn’t “feel” like proper ECS. After all, one of the main selling points of ECS is fast iteration and parallelization, but in this system, none of those were available at impressive speeds. So after looking at how normal ECS libraries like entt, hecs, bevy_ecs and specs crates did it, I gave it another shot.

Intro to archetypes

Instead of storing each component of my entities, per entity, I decided to implement a pattern called the archetypes system. This system groups each entity based on the types of components that it contains, or so called, its component “layout”. So entities with similar component “layouts” will be grouped in the same archetype (where component "layout" simply means an identifier for each combination of component stored on the entity).

Component Layout Example

For example, here is a table that represents our entities and components that are applied to them

| Entities | Transform | Health | Player |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entity 01 | X | ||

| Entity 02 | X | X |

assume that each component column (Transform, Health, Player), has an index to it that is incremented by one for each column. So the Transform column would have an index of 0, Health column would have an index of 1, Player column would have an index of 2 and so forth. We can calculate the component layout for each entity by simply marking what components are applied to it, which would look something like this (I will also show the component column index as well)

| Entities | Component Layout |

|---|---|

| Entity 01 | Transform (0) |

| Entity 02 | Health (1), Player (2) |

to calculate a unique identitifer for each combination of components, we can treat our component column indices as active bits inside a bitmask! So for Entity 01, the layout would be 0b001, since the 0th bit is enabled and no other bits (or components) are active.

For Entity 02, the layout would be 0b110, because it has the Health component (index of 1) and Player component (index of 2) (so, we must active the bits at indices 1 and 2, which gives us 0b110)

| Entities | Bitmask Layout |

|---|---|

| Entity 01 | 0b001 |

| Entity 02 | 0b110 |

The components will actually be stored within the corresponding archetype instead of loosely fitted somewhere in memory, which should improve performance. Whenever you add a component onto an entity, it calculates the new component layout (its bitmask) for the entity and “moves” it into the corresponding archetype (with the proper bitmask layout).

So in our example above, we'd have two archetypes, each containing one entity each. You'd have the archetype 0b001, that contains entities that only contain the Transform component, and the archetype 0b110, that only contains entities that have the Health and Player components. Something like this basically:

| Archetypes | Entities |

|---|---|

| 0b001 | [Entity 01] |

| 0b110 | [Entity 02] |

%%{ init: { 'flowchart': { 'curve': 'stepBefore' } } }%%

flowchart LR

A[Game World]

A --> AR1[Archetype 0b001]

A --> AR2[Archetype 0b110]

AR1 --> EG1

AR1 --> CG1

AR2 --> EG2

AR2 --> CG2

subgraph EG1[Entities]

E1[Entity 1]

end

subgraph CG1[Components]

CC1[Transform]

end

subgraph EG2[Entities]

E2[Entity 2]

end

subgraph CG2[Components]

CC2[Health]

CC3[Player]

end

%%{ init: { 'flowchart': { 'curve': 'stepBefore' } } }%%

flowchart LR

A[Game World]

A --> AR1[Archetype 0b011]

AR1 --> EG1

AR1 --> CG1

subgraph EG1[Entities]

E1[Entity 1]

E2[Entity 2]

E3[Entity 3]

end

subgraph CG1[Components]

subgraph ACC1[Transform Components]

CC1[Transform]

CC2[Transform]

CC3[Transform]

end

subgraph ACC2[Health Components]

CC4[Health]

CC5[Health]

CC6[Health]

end

end

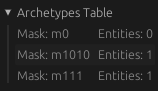

And finally, here's an actual archetype list from within cFlake engine

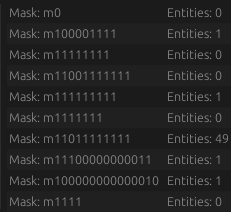

and here's a more complex case when loading the basic GTLF example

Memory Heap Allocation Optimization

By only allocating one archetype per component layout, we know beforehand what are the components we will store within them (due to their layout, which tells us the adequate components we will store eventually). As such, we can pre-allocate or deallocate memory that we do not need when needed. Another optimization you can do to further reduce heap allocations is instead of storing a Vec<Box<dyn Component>> (2 heap allocations: [Vec<_>, Box<_>], and the secondary one scales with the number of components), you could instead store a boxed trait object Box<dyn VecStorage> where VecStorage is implemented for every Vec<T> where T: Component (which reduces heap allocations to only two in total, no matter the number of components). This reduces your memory consumption by a lot compared to the previous because we aren’t constructing a dynamically dispatchable object for every component. Not only that, but it fits everything very tightly in memory, which also improves querying / iteration speeds, which is our next topic.

Query system

I made a simple “query” system (inspired, if not directly copied, from Bevy’s query system) that would allow you to iterate over any arbitrary mix of components stored in the world (through the help of tuples). So I could do something like the following:

// Iterating an immutable query that views all entities

// that have the Player component (immut) and Health component (immut)

for in ecs.

// Mutable query that iterates over all entities with the Transform component (mutable)

for transform in ecs.

Multithreading and Vectorization

By storing all my components within a vector for each component type, I can enable simple vectorization by looping over it normally, like any Rust iterator. I don’t have to deal with the old janky system of iterating through the entities, then fetching their components separately. This also meant this could be easily multithreaded by the help of the commonly used Rayon crate, which turns your simple threaded iteration code into multithreaded code very easily. This also makes multithreaded iteration extremely similar to single threaded iteration (the only caveat at the moment is the need to convert to an intermediate Vec<T>, but this could be fixed if you implement Rayon's ParallelIterator trait for all Query types).

// Mutable query that iterates over all entities with the Transform component (mutable)

// Need to convert to intermediate Vec<_> because I still haven't implement the ParallelIterator

// trait to my query types

let temp = ecs..into_iter.;

// Iterating over the vector in parallel (super fast, since all &mut references are linear in memory anyways)

temp.into_par_iter.for_each

Now unfortunately due to the nature of my game engine's world management (a global World that you'd access) there is no way to multithread adding multiple Entities or registering Archetypes (but even then, it wouldn't matter because there would an internal lock to keep things sequential, unless you make a copy fragment of the world on each thread, which would be an interesting thing to look into imo)

Change/Add/Removal Detection

Another commonly used feature within these ECS libraries is change/add/removal detection. This feature allows you to detect whenever an entities gets a component added onto it or when an entity’s component gets modified. I had to implement such a system to be able to handle procedural system generation, and after 2 iterations, I’ve got it working nicely for my use case. Here’s how I did it:

Initial implementation

I first did it naively: I stored 2 u64s (all my component indices use a u64 internally) for added / modified components for each of my entities. (I couldn’t handle removal detection due to the fact that it would need to dissociate entities from their components whenever they “hop” archetypes. Didn’t feel like coding that in so I opted with the easier solution of just not doing that lel). Here's an example of these two u64s that contain the added / changed components (where the first value contains the added components layout bitmask and the second value contains the changed components layout bitmask)

| Archetypes | Entities | State Masks |

|---|---|---|

| 0b011 | [Entity 01] | [0b001, 0b010] |

| 0b110 | [Entity 02] | [0b010, 0b110] |

So for Entity 01, we have an "added components bitmask layout" of 0b001 and a "modified components bitmask layout" of 0b011. This means that the component with the corresponding id of 0b001 was added onto the entity since last tick, and the component with the corresponding id of 0b010 () was modified since last tick

Inside my Archetype, along-side my entities vector, I also had a state vector that would store these two u64s for each entity within the archetype. I implemented this “filter” system (heavily inspired from Bevy’s filters) that would simply discard iterating over components that do not fit the given criteria based on these two u64s. For example, you could write the following filter:

// ``Bullet`` and ``Velocity`` are both structs that derive the ``Component`` trait

let filter = &

which would only iterate over the specified query for entities that have the “Bullet” components and a modified “Velocity” component.

The way I implemented this filtering system initially was very slow; I would iterate over my entities, check their state masks and do a bitwise and/or/xor (depending on the filter operation) on those and the new component mask. This is very wasteful because most of the time, those two u64s have only a few bits enabled in total, so a bunch of processing time is lost by computing something that wouldn't affect the final result.

Column based optimization

As an optimization, I thought of flipping things around. Instead of storing bitmasks per Entity, how about I store entities per bitmask?

Instead of storing 2 u64s for each entity, I store the state of each entity’s components in 2x u64s (where x is the number of components the entity has). I basically flipped this row based filtering system into a column based one, which allows me to compute the filter state of up to 64 entities all at once, only for the components that are actually needed.

The table below kinda shows this visually. Instead of storing the states for every possible component per entity, I only store the state of the actual components that the entities have (assuming all of these are part of the same archetype). And like the previous table, the first value represents the "added" state . The second value representing the modified state.

| Entities | Transform State Bitmask | Health State Bitmask | Player State Bitmask |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entity 04 | [0, 0] | [1, 1] | [1, 1] |

| Entity 05 | [0, 1] | [0, 0] | [1, 1] |

| Entity 06 | [0, 0] | [1, 1] | [0, 1] |

Since the possible variants for these values is either 0 or 1, we can "flip" the vertical columns into rows, and storing the values as bits inside a u64 chunk.

| Entities | Added State Chunk | Modified State Chunk |

|---|---|---|

| Transform State Bitmask | 0b011 | 0b011 |

| Health State Bitmask | 0b001 | 0b101 |

| Player State Bitmask | 0b010 | 0b011 |

I decided to modify the state array in my Archetype to a column state chunk array that contains the component add/modify state of 64 entities all at once (since there are 64 bits in a u64 integer) to. I could’ve went with u128, but for now I decided to keep it to a reasonable chunk amount of 64 (I could bump it up to 128 any time I needed anyways, it all makes use of the trait system so it is very easy to just switch to another type that implements the basic bitwise operations without having to rewrite most of the logic).

This sped up things incredibly, without having to complicate the code a bunch, so I’ll take it as a win. As an added bonus, I could now skip over a whole chunk (64) of entities if I know that none of them pass the filter (by simpling counting the number of bits inside the chunked state mask (which on most architectures, is a special instruction: popcnt)

Conclusion

And after uhhhh… a few months of painstaking blood shedding work and relentless nights of debugging non-deterministic tests and undefined behaviors due to manipulating raw pointers... there you go! You’ve got yourself your own proper ECS library!

(shoulda used one of the open source ones aaaaa)

oh well, at least it was a learning experience amiright ಥ‿ಥ

Other great resources that helped me learn ECS:

Medium.com article about building an Archetypal Based ECS

David Colson's article about making a simple ECS

C++ entt library

Rust specs Crate

Rust hecs crate

Rust bevy_ecs crate